Despite adamant declarations that I'd never let Nolan watch TV, a little bit of cartoon land has crept into our living room. It keeps Nolan mercifully out of trouble for 10-15 minutes while I whip around, preparing lunches and getting ready for the day. I knew the cartoons weren't good for him per se, but I didn't think they could inflict a serious condition on him.

Despite adamant declarations that I'd never let Nolan watch TV, a little bit of cartoon land has crept into our living room. It keeps Nolan mercifully out of trouble for 10-15 minutes while I whip around, preparing lunches and getting ready for the day. I knew the cartoons weren't good for him per se, but I didn't think they could inflict a serious condition on him.A startling Cornell University report has just revealed a perplexing connection between a toddler's time in front of the television and the likeliness of autism symptoms.

Though the television has been pondered as a possible connection to the increased incidence of autism (along with vaccines and environmental factors), it has never been proven. This is the first study that shows a direct link between television and Autism.

Studies suggest that American kids now watch about four hours of television daily, and it seems logical that the disorder would be related to something that has changed in kids lives in the past twenty years.

I know the study is preliminary and we shouldn't all hysterically throw our TV sets into the trash can but I think this is just enough evidence for me to ban Dora in the mornings.

Posted Monday, Oct. 16, 2006, at 6:52 AM ET

Listen to the MP3 audio version of this story here, or sign up for Slate's free daily podcast on iTunes.

Last month, I speculated in Slate that the mounting incidence of childhood autism may be related to increased television viewing among the very young. The autism rise began around 1980, about the same time cable television and VCRs became common, allowing children to watch television aimed at them any time. Since the brain is organizing during the first years of life and since human beings evolved responding to three-dimensional stimuli, I wondered if exposing toddlers to lots of colorful two-dimensional stimulation could be harmful to brain development. This was sheer speculation, since I knew of no researchers pursuing the question.

Last month, I speculated in Slate that the mounting incidence of childhood autism may be related to increased television viewing among the very young. The autism rise began around 1980, about the same time cable television and VCRs became common, allowing children to watch television aimed at them any time. Since the brain is organizing during the first years of life and since human beings evolved responding to three-dimensional stimuli, I wondered if exposing toddlers to lots of colorful two-dimensional stimulation could be harmful to brain development. This was sheer speculation, since I knew of no researchers pursuing the question.

Today, Cornell University researchers are reporting what appears to be a statistically significant relationship between autism rates and television watching by children under the age of 3. The researchers studied autism incidence in California, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Washington state. They found that as cable television became common in California and Pennsylvania beginning around 1980, childhood autism rose more in the counties that had cable than in the counties that did not. They further found that in all the Western states, the more time toddlers spent in front of the television, the more likely they were to exhibit symptoms of autism disorders.

The Cornell study represents a potential bombshell in the autism debate. "We are not saying we have found the cause of autism, we're saying we have found a critical piece of evidence," Cornell researcher Michael Waldman told me. Because autism rates are increasing broadly across the country and across income and ethnic groups, it seems logical that the trigger is something to which children are broadly exposed. Vaccines were a leading suspect, but numerous studies have failed to show any definitive link between autism and vaccines, while the autism rise has continued since worrisome compounds in vaccines were banned. What if the malefactor is not a chemical? Studies suggest that American children now watch about four hours of television daily. Before 1980—the first kids-oriented channel, Nickelodeon, dates to 1979—the figure is believed to have been much lower.

The Cornell study is by Waldman, a professor in the school's Johnson Graduate School of Management, Sean Nicholson, an associate professor in the school's department of policy analysis, and research assistant Nodir Adilov. "Several years ago I began wondering if it was a coincidence that the rise in autism rates and the explosion of television viewing began about the same time," Waldman said. "I asked around and found that medical researchers were not working on this, so accepted that I should research it myself." The Cornell study looks at county-by-county growth in cable television access and autism rates in California and Pennsylvania from 1972 to 1989. The researchers find an overall rise in both cable-TV access and autism, but autism diagnoses rose more rapidly in counties where a high percentage of households received cable than in counties with a low percentage of cable-TV homes. Waldman and Nicholson employ statistical controls to factor out the possibility that the two patterns were simply unrelated events happening simultaneously. (For instance, petroleum use also rose during the period but is unrelated to autism.) Waldman and Nicholson conclude that "roughly 17 percent of the growth in autism in California and Pennsylvania during the 1970s and 1980s was due to the growth in cable television."

But the fact that rising household access to cable television seems to associate with rising autism does not reveal anything about how viewing hours might link to the disorder. The Cornell team searched for some independent measure of increased television viewing. In recent years, leading behavioral economists such as Caroline Hoxby and Steven Levitt* have used weather or geography to test assumptions about behavior. Bureau of Labor Statistics studies have found that when it rains or snows, television viewing by young children rises. So Waldman studied precipitation records for California, Oregon, and Washington state, which, because of climate and geography, experience big swings in precipitation levels both year-by-year and county-by-county. He found what appears to be a dramatic relationship between television viewing and autism onset. In counties or years when rain and snow were unusually high, and hence it is assumed children spent a lot of time watching television, autism rates shot up; in places or years of low precipitation, autism rates were low. Waldman and Nicholson conclude that "just under 40 percent of autism diagnoses in the three states studied is the result of television watching." Thus the study has two separate findings: that having cable television in the home increased autism rates in California and Pennsylvania somewhat, and that more hours of actually watching television increased autism in California, Oregon, and Washington by a lot.

Research has shown that autistic children exhibit abnormal activity in the visual-processing areas of their brains, and these areas are actively developing in the first three years of life. Whether excessive viewing of brightly colored two-dimensional screen images can cause visual-processing abnormalities is unknown. The Cornell study makes no attempt to propose how television might trigger autism; it only seeks to demonstrate a relationship. But Waldman notes that large amounts of money are being spent to search for a cause of autism that is genetic or toxin-based and believes researchers should now turn to scrutinizing a television link.

There are many possible objections to the Cornell study. One is that time indoors, not television, may be the autism trigger. Generally, indoor air quality is much lower than outdoor air quality: Recently the Environmental Protection Agency warned, "Risks to health may be greater due to exposure to air pollution indoors than outdoors." Perhaps if rain and snow cause young children to spend more time indoors, added exposure to indoor air pollution harms them. It may be that families with children at risk for autism disorders are for some reason more likely to move to areas that get lots of rain and snow or to move to areas with high cable-television usage. Some other factor may explain what only appears to be a television-autism relationship.

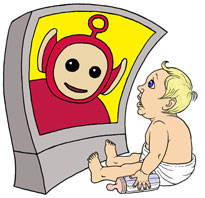

Everyone complains about television in a general way. But if it turns out television has specific harmful medical effects—in addition to these new findings about autism, some studies have linked television viewing by children younger than 3 to the onset of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder—parents may urgently need to know to keep toddlers away from the TV. Television networks and manufacturers of televisions may need to reassess how their products are marketed to the young. Legal liability may come into play. And we live in a society in which bright images on screens are becoming ever more ubiquitous: television, video games, DVD video players, computers, cell phones. If screen images cause harm to brain development in the young, the proliferation of these TV-like devices may bode ill for the future. The aggressive marketing of Teletubbies, Baby Einstein videos, and similar products intended to encourage television watching by toddlers may turn out to have been a nightmarish mistake.

If television viewing by toddlers is a factorin autism, the parents of afflicted children should not reproach themselves, as there was no warning of this risk. Now there is: The American Academy of Pediatrics currently recommends against any TV for children under the age of 2. Waldman thinks that until more is known about what triggers autism, families with children under the age of 3 should get them away from the television and keep them away.

Researchers might also turn new attention to study of the Amish. Autism is rare in Amish society, and the standing assumption has been that this is because most Amish refuse to vaccinate children. The Amish also do not watch television.

Correction, Oct. 17: Steven Levitt's name was misspelled in the original version of this article. (Return to the corrected sentence.)

No comments:

Post a Comment